Have you ever felt chills ripple down your arms while listening to music? Or found yourself unexpectedly moved to tears by a performance, even though you knew exactly what was coming next? These moments are not sentimental exaggerations. They are deeply neurological and profoundly human. Scientists have a name for this sensation: frisson.

Frisson: When Art Reaches the Nervous System

Frisson (from the French word meaning “aesthetic shiver”) refers to the physical reaction some people experience when encountering something emotionally powerful in music, visual art, or performance. Goosebumps, chills, a tightening in the chest, even tears—all of these are signs that the brain’s emotional and reward systems have been activated.

Neurological studies show that frisson occurs when areas of the brain associated with pleasure and emotion—particularly the dopamine reward pathway, the amygdala, and the nucleus accumbens—fire in response to moments of surprise, beauty, or emotional intensity. Music that shifts suddenly in harmony, dynamics, or texture is especially likely to trigger this response.

A visual representation of frisson, showing how music activates the brain’s reward and emotion centres. When dopamine is released in areas such as the nucleus accumbens and amygdala, listeners may experience chills, goosebumps, or an intense emotional response to sound.

Research suggests that between 55% and 86% of people experience frisson at least occasionally. It appears more frequently in people who are highly empathetic, emotionally open, and deeply engaged with the arts. In other words, when art feels overwhelming, it’s because your brain and body are responding exactly as they were designed to.

When Beauty Arrives Before Language

I’ve experienced frisson many times while listening to music—those unmistakable shivers that seem to arrive before conscious thought. But one of the most powerful moments happened in the theatre.

Watching the opening scene of The Lion King on Broadway, I was completely overcome. As the music rose and the stage filled with movement, colour, and sound, tears came instantly, not from sadness, but from awe. It was as though the beauty of the moment bypassed logic entirely and went straight to the nervous system. It reminded me that our responses to art are not always tidy or verbal. Sometimes our bodies understand something before our minds can explain it.

Seeing Sound: Synesthesia and Crossed Senses

For some people, the experience of art goes even further, crossing sensory boundaries altogether. This phenomenon is called synesthesia—a neurological condition in which stimulation of one sense automatically triggers another. Someone with synesthesia might see colours when hearing music, associate letters or numbers with specific hues, or experience sounds as shapes or textures.

Synesthesia is estimated to occur in about 2–4% of the population, though many people don’t realize they experience it until later in life.

One of the most famous artists believed to have synesthesia was Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky described hearing colours and seeing sounds, and he believed that painting could function like music—capable of reaching the soul directly, without representing the physical world. His abstract works were attempts to paint inner experiences rather than objects.

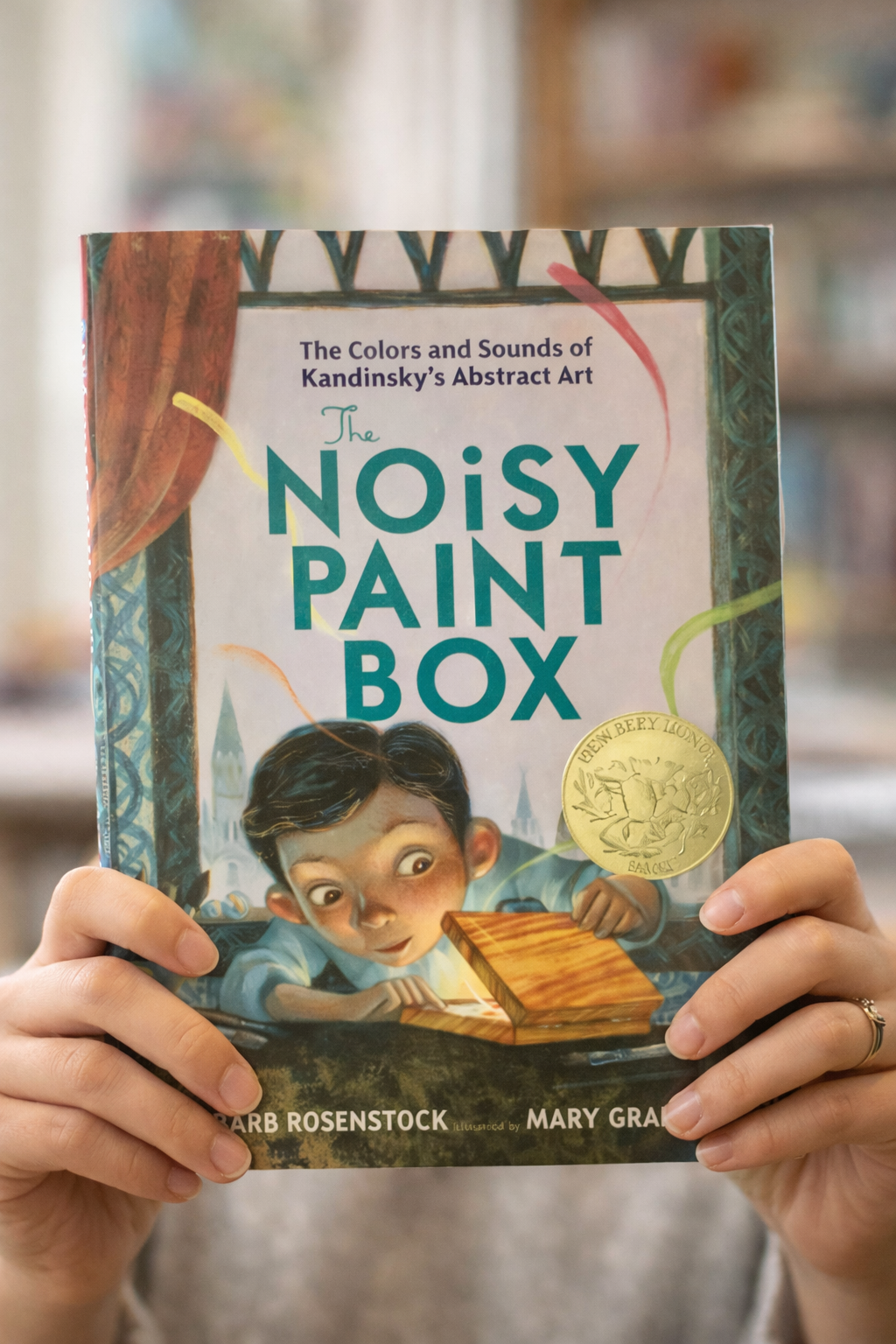

This idea is beautifully explored in The Noisy Paint Box, which tells the story of Kandinsky as a child discovering that he heard colours when he listened to music. In the book, adults initially tell him that sounds aren’t colours—that what he’s experiencing isn’t “real.” Yet it is precisely this inner world that eventually shapes his revolutionary approach to art.

The message is powerful: sometimes creativity begins when we trust experiences that don’t yet have words.

The Noisy Paint Box: The Colors and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art by Barb Rosenstock, illustrated by Mary GrandPré. This book invites readers to explore how Wassily Kandinsky experienced sound as colour—and how trusting one’s inner perceptions can lead to powerful creative expression.

Colour, Harmony, and Making Sense of Sound

I don’t experience full synesthesia, but I’ve noticed something revealing in my own relationship with music. When trying to harmonize, I struggled—until I began to visualize the sound. The only way I could hold a harmony line was to imagine the melody and harmony as two intersecting lines of colour, moving alongside one another. Once I could see the relationship between the notes, I could hear it and sing it. This experience reinforced something important: art is not processed in a single place in the brain. It is embodied, visual, emotional, and deeply personal.

An abstract interpretation of musical harmony, visualized as intersecting waves of colour. For some listeners, understanding harmony becomes easier when sound is imagined visually rather than aurally.

Why This Matters in the Classroom

For educators, phenomena like frisson and synesthesia offer a powerful entry point into arts education. They shift the conversation away from “Do you like it?” or “Is it good?” and toward a more meaningful question: How do you experience it? Inviting students to reflect on their own sensory and emotional responses validates their inner experiences and helps them understand that there is no single correct way to engage with art.

Teachers might ask:

Have you ever felt chills or strong emotions while listening to music or watching a performance?

Did your body react before you understood why?

If this music were a colour, what would it be?

If this artwork had a sound, what might it sound like?

Do you think everyone experiences this piece the same way? Why or why not?

These questions encourage awareness, empathy, and self-trust.

Reading The Noisy Paint Box alongside a Kandinsky-inspired art lesson, pairing music with abstract painting, or inviting students to write about moments when art made them feel something physically—all of these approaches reinforce an essential idea: our responses to art are real, meaningful, and rooted in biology.

Art Lives in the Nervous System

When we teach students about frisson, synesthesia, and artists like Kandinsky, we are doing more than teaching art history or neuroscience. We are telling students that their experiences matter, that the shivers, the tears, the colours they imagine, and the emotions they can’t quite explain are not distractions from learning. They are learning. Art doesn’t just live on the walls, the page, or the stage. It lives in the nervous system. And sometimes, it announces itself with goosebumps.

References/Further Reading:

Blood, A. J., & Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(20), 11818–11823.

Salimpoor, V. N., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K., Dagher, A., & Zatorre, R. J. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 257–262.

Huron, D. (2006). Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. MIT Press.

Cytowic, R. E., & Eagleman, D. M. (2009). Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia. MIT Press.

Simner, J., Mulvenna, C., Sagiv, N., Tsakanikos, E., Witherby, S. A., Fraser, C., Scott, K., & Ward, J. (2006). Synaesthesia: The prevalence of atypical cross-modal experiences. Perception, 35(8), 1024–1033.